Over 41,000 children in Nova Scotia are living below the poverty line.

This according to the recently released 2020 Report Card on Child and Family Poverty in Nova Scotia, a report based on the most recent income-based statistics from 2018.

The report shows a jump in the percentage of children living in low-income households from 2017 at 24.2 per cent to 2018 at 24.6 per cent.

This amounts to 41,370 kids living in poverty in the province.

“I struggle to find the words to describe how I feel about that,” said Lesley Frank, primary author of the report and Acadia University Professor said in a press release.

“I move between anger, sadness, to embarrassment – and an overwhelming sense of worry for families struggling through hardship now.”

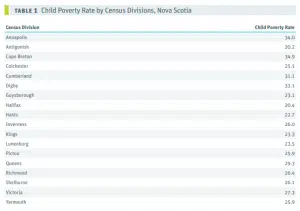

In a breakdown, the report shows the higher rates of poverty coincide with areas that are more rural than others, with the highest rates going to Cape Breton (34.9), Annapolis (34), and Digby (33.1).

A number of factors contribute toward child poverty being higher in rural areas of the province, said Heather Fraser, executive director for the South Shore Family Resource Association.

Those include limited employment opportunities, food insecurity, lack of health services, limited affordable childcare, and transportation among others.

“There’s no transportation in some of our real rural areas, so if you can’t get to where you’re going, you can’t work,” she said.

“Also many areas in rural Nova Scotia struggle with safe affordable housing, with some having absolutely no affordable housing available. This means some families can’t even look for a better place to live because there are no better places to live.”

A table from the 2020 Report Card on Child and Family Poverty breaking down rates by census divisions.

On the South Shore, poverty percentage rates for children remain high, with the more rural counties of Queens (29.3) and Shelburne (26.1) sitting above the provincial rate, while Lunenburg (23.5) sits just below.

The report also shows child poverty rates have stayed in the same general range since 1989, the year the province promised to eradicate child poverty by 2000.

The increased and lasting rate of poverty in Nova Scotia, said Fraser, is largely systematic. However, a lot can be done from any level of community to start reducing those rates, she said.

“We, as in government, organizations and community members, need to do a better job of supporting our most vulnerable populations,” she said.

“We need to be mindful to provide that support in a respectful, non-judgmental and non-stigmatizing way. I feel that is the first step. We know the system moves slow, so I feel communities need to step up to the plate and support those families in need.”

Currently, Nova Scotia has the third-highest provincial child poverty rate in Canada, and the highest in Atlantic Canada.

According to the report, if measured with Canada’s official poverty line (the Market Basket Measure), Nova Scotia sits at the top with the highest child poverty rate at 14.8 per cent.

Fraser suspects that rate will continue to raise for this year due to the economic and financial effects of COVID-19, which resulted in mass layoffs and job loss across Canada.

However, there is a lighter side to the pandemic that has made itself visible in most communities, said Fraser.

“Throughout the pandemic, the communities have stepped up in the areas we serve and have provided a vast amount of support to families who need it,” she said, “It’s just so heartwarming to see.”

But, without support from the provincial government, efforts elsewhere may be wasted, said the report.

“Very little has changed to support families with children living in poverty,” said Christine Saulnier, Director of the Nova Scotia office of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives on the report’s recommendations to government.

“While the data in this report card is for 2018, we can predict that–just like we did two years ago, without significant investment by our provincial government in income supports, any small gains in one year are lost in the next.”

Follow Cody McEachern on Twitter at @CodyInHiFi for more